Tues July 27

We wake to a fine weather day, lots of blue sky, only minor wisp of cloud cover hangs around the Sverdrup glacier. It’s a day hike to explore Cape Hardy and vicinity, searching for the remains of Frederick Cook’s over wintering camp, 1908- 1909. Cook and Peary raced each other to be the first to the North Pole – now there are doubts if either man really made it. We pack gun, rain gear (just in case), lunch and cameras and head out.

The easiest walking is to stay high on the raised beaches where the tundra is dry and firm, avoiding the labyrinth of small ponds and wet spots on the draining plain. Eventually, at the last possible place, we will cut down to the ocean beach. Almost immediately, we come across a herd of eight muskox – the bull is grazing far down on the plain but he spots us 1 km away from his herd – fur flying, he sprints across the tundra to protect his group. They circle around their young calves as we approach. At 100 meters, they wheel and run higher up into the hills.

It’s another three km until we descend to Brae Bay. We keep an eye out for Inuit longhouses, boulder structures of massive dimensions, the article said 10 x 40m! however, we find nothing but four snowshoe hares nibbling green grass. We continue walking along the beach and low cliffs until the tip of Sverdrup glacier comes in to view…more lowlands and flats and more muskox. With limited energy, we decide to concentrate on Cape Hardy instead of pursuing this eastward direction. Sverdrup glacier will have to wait for another time.

The shore line is littered with the remains of modern exploration – aviation fuel drums, cut lumber, skidoo tracks in the gravel, smallish rocks outline tent footprints, the occasional shotgun shell. I’m surprised at the number of whale vertebrae and pieces of bone part that poke out of the gravel shore. Brilliant orange lichen, latched on decayed bone in thick clumps, is a colour shock to the eye. No skull or ribs are evident, having already been scavenged or not yet exposed. Do Grise Fiord hunters still come this way? Hunting for what I wonder…

It’s a beautiful day! the sun is shining in full force, sparkling waters between broken ice flow chunks. There are no bugs and its mostly wind calm. How quiet it is, I hear water droplets fall as they melt in to the salt water. Slowly we pick our way out to Cape Hardy…there is a long narrow isthmus that barely connects the cape to the mainland, the land rebounding from glacial retreat. Long gravel bars of loose packed rock bridge the gaps but there seems to be more water than land.

How quiet it is, I hear water droplets fall as they melt in to the salt water. Slowly we pick our way out to Cape Hardy…there is a long narrow isthmus that barely connects the cape to the mainland, the land rebounding from glacial retreat. Long gravel bars of loose packed rock bridge the gaps but there seems to be more water than land.

Cape Hardy itself is an imposing mountain of stone that towers over our heads, rising dramatically of the sea to a peak of 800 feet. Red rock walls fracture into heaps at the base of cliffs, a small terrace of slightly sloping ground tilts towards the water. Thousands of white shell fragments have either been washed against the cliffs or else were originally deposited there when water levels are higher. A third possibility is gulls or ravens have dropped the shells here in an effort to crack them and thus obtain access to the interior muscle meat. Very quickly we discover the remains of rusting steel leg hold animal traps, modern tent rings and more bones. It seems to be a popular seasonal hunting spot still very much in use (Pepsi cans). Fat arctic hares dot the slopes, their white coats giving them away.

We don’t know the exact location of Cook’s site but make a guess that it would provide an ocean view in order to signal passing whaling ships. We head to the eastern most point, clambering up and down and around, searching for any hint of a winter camp. Enroute I find the ancient skull of a polar bear. It’s black with age and green moss, a huge skull with massive center ridge, and missing the lower jaw. One front incisor is chipped but the ivory threat still gleams in the sun. I respectfully place him back in the groove where I found him.

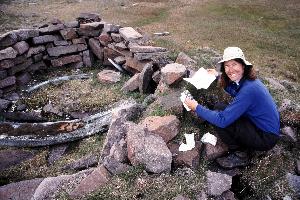

The beach disappears and the same rock scramble as on Cape Skogn starts, up and down and around. Finally we reach the eastern most tip of the cape. A small green meadow, surrounded by ice on three sides, juts into frozen Jones Sound. Even from this distance and elevation, I can see piles of rocks stacked by human hands. This must be the Cook site! Excitedly, we start to look around, quickly finding two or three collapsed sod houses. Whale bones, ribs – skull pieces – vertebra are scattered around. Other bones from walrus – dog or wolf – polar bear – muskox - seal are mixed together. Nestled in a deep cranny beside the best preserved house is a fox chewed plastic peanut butter jar. I open it to find inside, photo copied pages from the Frederick A. Cook Society website, detailing Cook’s wintering stay here. Hallelujah! We marvel at the tenacity to winter here, Inuit or white man, living in a small dug out shelter through the long arctic winter. We spend hours, sitting inside the sod houses, looking out at sea, the ice, Devon Island then laying on our backs, listening to the voices of those who lived here.

Eventually, getting cold and hungry, we retrace our steps back along Cape Hardy’s rocky beach, cross the narrow land bridge to the mainland and the beeline back to camp. The weather has started to change, the high overcast has thickened and fog is starting to build. By 10pm, we have dinner and hash over events of this long and exciting day. One last look around before heading into the tent – pots and other small gear are stashed under the tent vestibule for the night - rain looks imminent.