Glaciers as Gate Keepers

Gorgeous and beautiful, glaciers were (and still are) a landscape feature that I, as a Southern Ontario resident, had had zero experience with. Oggling their mystery and majesty was one thing but traversing their slippery slopes filled me with trepidation. My imagination ran wild, fueled by hair raising tales told by other adventure travelers. Glaciers were dangerous high risk places, braided with lurking bottomless crevasses waiting to gobble up the unsuspecting. Yikes! Literature provided by Parks Canada ominously talked about the need for ropes, crampons, experienced guides. Here we were, on our little own, looking into the belly of the beast. Nervously, my heart pounded.

I had mentally subtitled this trip as ‘the glacier tour’. Every day and in about every direction, you could see some part of a some glacier. Of the several recommended hiking paths between Lake Hazen and Tanquary fiord, we opted to follow a route where glacier crossing skills would not be needed. Ha! Things didn’t turn out exactly as planned.

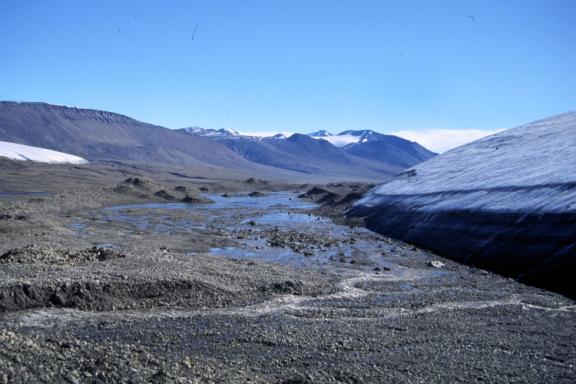

Last night we set up camp under a gloomy grey overcast 2 km away from the Scylla – Charybdis (a lobe of the Viking Ice Cap which extends northward into the Lewis River Valley) glacier gap. These two glaciers served as gate keepers to Ekblaw lake, the route down the Air Force River valley and out to Tanquary Fiord. The route suggested on the Park map showed two choices: up and over the Scylla glacier or sneak between it and Charybdis glacier. As glacier neophytes, we opted for the more prudent safer ‘sneak’ route…

By morning, the skies had cleared and eagerly we packed and departed camp. Scylla glacier gleamed in the fresh air. Rock hoping or leaping over smaller streams is easier in the morning when melt water volumes are at their lowest.

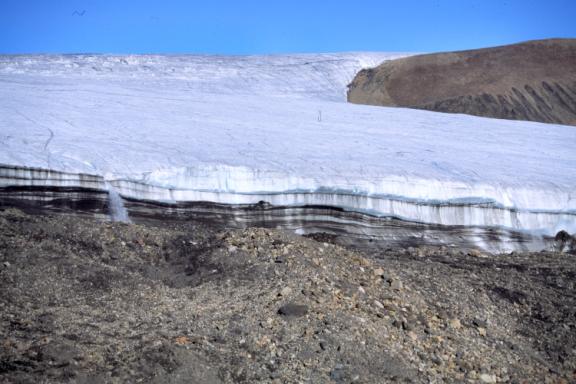

(photo above) This is the head of the Lewis River valley. The Charybdis glacier (in the photo) is located on the north side of the gap and the Scylla glacier on the south side. Note the steep glacier sides of the Charybdis and the mounds of loose rock at its toe – easier passage was to be found along at the Scylla side of the gap.

Heads bend down, eyes scanning the ground, we pick our way between Scylla glacier toe and rock debris, looking for gravel pieces firmly melted into the ice for maximum traction.

Eventually, walking along the toe became too difficult as the ice slope steepend, the boots lost traction and our feet began to slip sideways. The choice was now to plow through the rocky rubble or try and climb the glacier toe up, across and then down. After a few steps, we gave up on the rocky slope: it was too steep as with each step up, the slope crumbled underfoot.

Dumping our packs on top of some dry boulders, we hunt along the toe, searching for a place to scale where the rock imbedded surface would take us high onto the body of the ice. Of course we could not see the top but it didn’t really matter as being having no prior glacier experience, we couldn’t judge good surface from bad.

Wow, these things are BIG! Ron pauses at the toe of the Scylla glacier toe, a water rutted outflow to Ron’s right…the flow disappearing quickly into the rock rubble at its base. It’s a hungry land that eats water and people with equal opportunity.

As well, scaling the glacier with hiking boots is possible for the first 4m as the grey rocks provide purchase for bare boot soles but as the slope gets steeper and there are no rocks, the ice is polished bare by repeated sun melting and night cooling.

Carefully we crept up, me scrambling with my hands occasionally. It took only about 10 minutes before we rounded the toe’s curve to the flatter main body of the glacier. We were richly rewarded by the most stunning views of the Ekblaw valley to the north. The sun shone, I felt like I was on top the world without a care - everything would be easy after this (ha ha). We scouted about 250m, snapped some photos and easily skidded down the toe, retracing the way we came up.

It was not exactly easy climbing up the toe again this time with our heavy backpacks. A few more slips, a few grunts, a few choice words and finally we arrived at the same plateau. From there, we moved slowly along the glacier contour, not wanting to climb any higher than necessary.

Across from us, waterfalls poured over the lip from the Charybdis glacier, tumbling several hundred meters to the rock rubble below. Moved by the force of the water, rocks grinding against each other, pulverized into fine sand before washing down into the Lewis River valley downstream. A growing suspicion builds as to what await our decent from the Scylla Glacier. Again, the map is unclear on this detail. Blindly, we trust the descent will be similar to the ascent up the toe…

Walking becomes more difficult. The glacier surface gets more and more slippery. Under a cloudless sky, burning rays of the mid day sun have melted any remaining soft surface away and expose the slippery permanent ice cap – footing is treacherous and more than once, my poles save me from taking a header. Its time to get off.

The junction of ground and glacier toe is not visible due to the curve of the glacier. We will be descending blind and none of us like it. What if there is no rounded toe but a sheer drop like the waterfall slope of the Charybdis glacier? There is a sound of running water but we can’t see how big or where it is. Jack takes off his backpack and tentatively slides it down over the curve: it disappears from sight – we count 1 – 2 –3 seconds before we hear a thud. Hmmm…foolishly, we decide to risk the blind descent.

Jack goes first, squatting down on the back of his boot, heel digging in as a break, the other leg outstretched for balance and to break the worst of any fall. Ron and I wait, watching as Jack slides out of sight…then with a sudden ‘hurrah!’, we smile and know its OK. Ron goes next and I follow.

What did I learn from this episode? One, don’t blindly trust the map as conditions might have changed since they were published. Two, an isolated wilderness trip is not a good time for foolhardy antics under life threatening duress. Three, eat the ego and ‘go back’ despite the extra effort sometimes required.

We were damned lucky, descending at this spot and we all knew it – just 50 metres further along, the glacier toe ended as a sheer drop into a boulder filled torrent of rushing ice cold water. Phew….I gave thanks to my lucky star.