Animals: It’s a (n arctic) jungle out there!

One of the carrots that enticed me to visit Ellesmere Island Nat Park was the potential for wildlife encounters. I had read that the animals were so unfamiliar with humankind, they were fearless and didn’t flee at the first sight of a human being. I found it hard to believe that an animal would not just run at the sight (or smell) of us big hairy apes. Stories of curious foxes and fearless wolves that approached, sniffed and then peacefully retreated stirred the junior naturalist in me. Was it so in the biblical Garden of Eden?

With no trees, visibility can extend to the horizon, all movement naked to the careful observer. I loved just sitting quietly after camp had been pitched, in the wind shelter of a large boulder, bino’s in hand, scanning for wildlife. Happily content, I could view animal behaviour as it unfolded, undirected by human intervention. No feeding stations, no baiting, no food enticements. On this trip, I was hoping to see wolves up close, foxes, muskox, many artic birds and arctic hare. Park literature made some noise about polar bears but I tossed this off as hyperactive cover-your-ass bureaucracy.

Musk Ox

Related to the goat family, these fleet footed inhabitants of the high arctic were found in abundance around Lake Hazen. We spotted them almost immediately from the air, their characterstic brown coats well visible against the green sedges and meadows where they like to feed.

Small groups from 8 to 15 animals hung around to the north of Hazen Lake base camp. We were preoccupied with finding our way up the Snow Goose river valley (navigation issues) and didn’t pay them much attention. At the head of the Snow Goose, they had largely disappeared from casual inspection but a few lingered, like this group of three, near our campsite. Clumps of qiviut fur stuck to boulders where they had brushed and also along outcroppings along the river banks.

Evidence of generations of musk ox occupation was everywhere. Bones bleached white glowed from kilometers away. Heavy skulls topped by well knacked horns, the tundra decorated by loose teeth where sometimes all that remained. Bones and skulls showed up in unexpected places, like 3000’ up on the Ad Astra ice cap.

A tang drifted in and out of my nostrils for kilometers. With so little organic matter and no atmospheric pollution, my nose had become sensitive to the slightest odour (especially hiking feet, fragrantly ripe and released from their day time prison of gortex boots).

After some searching, the not too long dead carcass of this adult muskox was found, maggoty guts spilled. Mostly fur remained plus feet, skull and larger bigger bones. Dotted around where generous piles of wolf excrement interspersed with smaller tokens of fox leavings. Cause of death unknown. .

Arctic Wolves

The one animal I really wanted to see but did not, was a wolf. Their tracks teased me, running up and down the beach, circled the tent, evidence of their quiet night visits. We brought the hiking boots into the tent each night so no curious wolf could snatch one off, and chew the salt impregnated sweat leather. Maybe I should have left one outside after all…

‘bunny explosion’…all that is left after an encounter from with a wolf

The wolves preyed mostly on arctic hare (very plentiful), lemmings (small mouse sized rodents), musk ox and perhaps caribou (but with small populations, they couldn’t have be a staple food source).

Ironically, it was on our homeward flight, in Eureka, (a research base and weather station) where I saw my white arctic wolf. They had been habituated to human food and were more like pet dogs, sniffing around for food scraps outside weather beaten doors. Somewhat sadly, I looked but couldn’t bear to take a photo.

Arctic Fox

The delicate arctic ecosystem vibrated with even the slightest intrusion. My footprints were invisible only to me as creatures in the area were aware of my presence. Inadvertently, I altered animal behaviour with out wanting to do so.

Writing in my journal, I chanced to glance out the open tent flap. A furry arctic fox nosed around, investigating the dinner site. It had been mac and cheese: sloppily, some tiny dehydrated crumbs of ham had fallen out of the plastic bag. Collecting what I could find, I brushed them off and threw them in the pot to hydrate. The fine and sensitive nose of the fox found where they had touched the ground. I watched as he cautiously crept, keeping low, silky coat feathered by the light breeze. His beady eyes locked into mine as he tentatively chewed the fallen morsels – a few seconds and gulp, they were gone. Next, he tested the herbal tea bag, left to dry out, overnight. He mouthed it and then disgustedly spat it out. I laughed…he raised his bead, we locked eyes and I swear he smiled before scampering off.

Birds

Somewhere I came across a list that itemized the ‘10 most common birds on Ellesmere Island’ …well, for sure I could identify different terns, gulls, ducks and loons, honking and squawking at various times of the day (and night) in and around Lake Hazen. Long tailed jaeger? eh? I don’t recall seeing any jaegers but then I’m not sure I would have recognized one anyhow. On the land, black and white snow buntings flitted just about everywhere and the clucks of ptarmigan were heard (although rare to see). With no bird book (hikers weight restriction), some of the bird identifications were guesses. However we did see many red knots and ruddy turnstones.

It was interesting to watch the birds develop through the short summer season. Arriving in late June, the nests were loaded with eggs. During the next seven days, the eggs hatched and young chicks would dash off, hiding between rocks or sheltering amongst a clump of grass. We were careful when walking and setting up camp to avoid damaging any nest. If too close, Mom bird would engage in a broken wing display or run or chirp-trill-shriek-call to draw us from her defenseless young.

One day, on the long walk towards Tanquary Fiord, I was sitting, propped up against my pack, resting. This young bird hopped over my boot, intent on chasing some insect (I guess). With a small effort, I caught the young chick and gently held him for a few seconds. His head bobbed too and fro but not a peck to my fingers. Carefully setting him down, he instantly resumed his hunt, none the worse.

Arctic Hares

Seeing arctic hares (‘ukaliq’) was straightforward as they were plentiful – but getting close was a challenge that I never really mastered (think ‘patience while trying to ignore buzzing bugs). They were unbelievably large (7 to 15 lbs), the body volume exaggerated by fluffy white fur, long ears and longer white legs. The colour of their coats remains white all year round as the summer season was too short for a moult and regrow.

Conspicuous white dots, groups of sometimes 50 animals would be browsing, playing, resting while a few self appointed sentries kept an eye open. Rearing up on their hind legs, they can run at up to 60 kph which is needed to escape their number one predator, the wolf.

.

.

Peary Caribou

Peary Caribou are fairly rare on Ellesmere Island, as their population has being decimated by explorers and adventure seekers like Robert Peary (ironically whom they are named after) and more recently, changing climate conditions (again ironically, fewer days above zero produce more freeze-thaw and ice layers which prevent them from breaking through the crust to reach lichen and other winter foods). Their population in the Park was not robust, so it was thrilling to come across a group of eleven.

We were walking deep in the valley, along a tributary of the Snow Goose River. I paused, scanning the creek bed for an easy way to cross and noticed large white dots on the distant slope. Hauling out the binos, I first thought ‘arctic hare’ although they didn’t look quite right. To my surprise and delight, they were caribou! We quickly dumped the backpacks and start to climb up the slope, hoping they would not run away as we approached.

Hot and sweaty after an hour of hard uphill walking, fortunately the slight breeze kept the mosquitos down and maybe diluted our scent to a less offensive odour. There are six large animals with antlers, 3 without and 2 small juveniles who dance and play with each other, bravely approaching us the closest (within 20 meters). When the animals start to get skittish, we sit down and wait. They relax and continue to feed…a small group of 8 or so arctic hares are also feeding on the same slope, and from our perspective, the hare look larger than the caribou!

So we sit and watch and wait and watch, taking a few photos then taking no more photos then just soaking up the moment. Between feeding, the caribou snort and kick and grunt at each other. Ribs protrude under lank shedding winter coats. The hare browse the same slope as the caribou, both seeming to ignore the other. After 60 minutes, we slowly back away, leaving the caribou and hares undisturbed. Elated, I skip back down the slope, not minding the long walk and for once, heavy backpack waiting.

A Final Cautionary Note

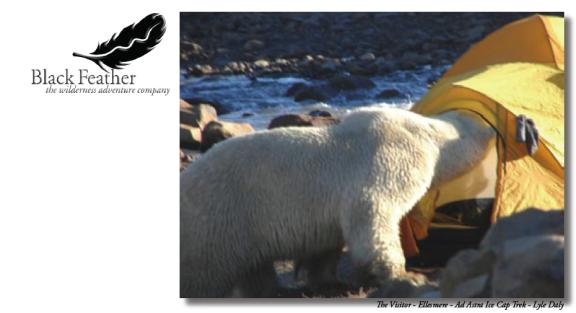

The routes we did were completely inland except for the last day where we camped along the shores of Tanquary Fiord in the Park base camp. I certainly never expected to see a polar bear in our travels and certainly the Park Warden did not mention any bear activity in the park. It was with great surprise that I learned about a guided trip in 2006 or 2007 which encountered a polar bear in the Macdonald River valley. Luckily, no one was hurt including the bear but it just goes to show that those white bears do wander unpredictably. With a ‘no gun’ policy in all Canadian national parks, including this northern arctic park where polar bears do range, future travelers be warned.