Snowshoe!

I awake at daybreak, 6am, sun light bouncing around the pale wood walls of the cabin. Feeling refreshed but lazy, I roll over to grab another few hours shut eye. By 8am, most people are up and moving around slowing, dressing, outside for a pee behind rocks, heating water for breakfast. Our leisurely breakfast of oatmeal, biscotti and oysters is washed down with tea, then packing begins. After a bit of reorganizing, everything has found a place in our backbacks – phew! We take the first tentative steps…

It’s slightly overcast outside, a thin grey cloud cover that diffuses the light. At –15C and wind calm, its pleasant going. I estimate our backpacks weigh about 45 lbs / 20 kg each. The first 400 meters we don’t even bother with snow shoes as we follow a hard packed dog sled trail. After that, we split off the trail and move in to virgin snow pack. The going is somewhat soft as it is sea ice – the tide has cracked the frozen surface of the sea and water has seeped between the cracks, dampening the snow. Small rock islands are bare of snow, their bases circled by blue-green melt water. Spring is certainly in the air. Thoughts of falling through rotten ice cross my mind….hopefully the snow shoes will distribute my weight with loaded backpack and this will not happen. Still, the ‘what if’ scenario plays through my mind until I gain confidence and fears are forgotten.

Ski tracks appear and we take advantage of their packed surface. Later we find out that a group of 5 French skiers passed this way a few days earlier. It takes about 30 minutes to travel one flat kilometer – a similar slow pace compared to hiking with a pack, off trail, in say Labrador.

The first challenge looms ahead – it’s a 400m climb up from sea level over a distance of about 2.5 kilometers. The last pitch is brutal: the snow is soft, piled up against a rock ledge and melting. I post hole with snow shoes and its worse without. The route up follows a frozen creek, the snow pockmarked by others who have gone before us, frozen ruts providing little grip for the snow shoes. Gasping for air, I take 50 steps then stop for 10 seconds before repeating at least another 10 times.

The views looking back over the frozen fiord and across to the Palerfik site are great. Snowy bowls, a frozen creek caught in mid flight, we are higher than the Avannarleq glacier at the end of the fiord. Hugging the contour lines, we cut off to follow a tiny creek which goes straight up. With no poles, I grab instead onto rocky crags alongside the gap. Sweating, the wind keeps me moving as I start to chill out.

Finally, about noon, we reach the top. At long last, the elevation has leveled out. Boulder erratics dot the ridges, dropped by retreating glaciers from the last ice age. The snow cover is deep enough to cover bare rock, so conditions are good for snow shoeing. However, it is noticeably colder and windier up here at 400m compared to sea level. It’s a short 2 minute stop before loading up and moving on.

We descend a short steep slope to a small chain of ponds. How nice to go down! My leg muscles thank me, happy for the change. Sheltered behind a large boulder, it’s a hurried lunch of cheese, nuts, fish can and a few sips of cold water before moving on. Every so often, a peep of blue sky shows between a layer of thin wispy strands and fast flying cotton ball clouds.

Dog sled tracks now mix with the ski tracks. Why were people saying we would get lost? These ruts are well visible but perhaps with fresh snow…this plateau between watersheds is short. Already, we reach have reached the lip of a waterfall, a serious downward drop with hard back snow on top of flash frozen green waters. It’s a rocky defile, cliffs 430m tower above us. We wind between the narrow groove, less than one meter wide in places. How does a sled manage to get through? The skiers appear to have walked, as I see their boot prints.

At one point, the hill is so steep, I take my pack off and simply toboggan it down the slope, skiing down on the metal heels of the snow shoes. Alfred lets his pack rolls down as well but takes off his snow shoes, walking down the hill. The contrast between flat plateau and this crack is stark - what a scenic one kilometer!

Eventually, the tortuous water course opens up to a broader valley. It’s a beautiful view looking east, the ice colour of frozen blue green water falls unbelievable. Willow twigs poke up from the valley floor, leveled by snow layers and easy walking. It’s a magical place, a secret, frozen Eden. Small red rocks poke through thin snow cover but so covered with lichen they appear to be black. It’s ohhh so quiet except for the deep throated croak of ravens, high up on their cliffside roosts. No tracks of fox, ptarmigan or hare.

I take the snowshoes off but after a few steps, put them back on. Although the snow layer is shallow, they ‘float’ me on top the surface and its much less tiring to shuffle along compared to lifting my feet the 2” higher without snow shoes. Water has seeped from shallow green ponds, tuft of yellow straw grasses poke holes in crusty snow. Soft mud and mosses are visible where the snow has melted away, revealing tundra below.

After about 3 kilometers, the narrow valley opens into Qororsuup Tasia (a lake). Flemming hut, our nights destination, is at the far north end. We take a 10 minute break, enjoying the wind still air, warm sun on cheeks, a few cookies and hot water from thermos. A few komatik tracks run across the lake, going in the direction of Ilulissat.

Interesting that the lake ice is much firmer than the sea ice – must be the fresh vs salt water. The lake surface has been largely blown clear of snow, and I start to look for snow patches as they offer easier grip and more comfortable than concrete hard bare ice which jars my bones with every step. Squinting hard, the sun’s glare from the bare ice is annoying – luckily our direction of travel is northerly and not directly westward.

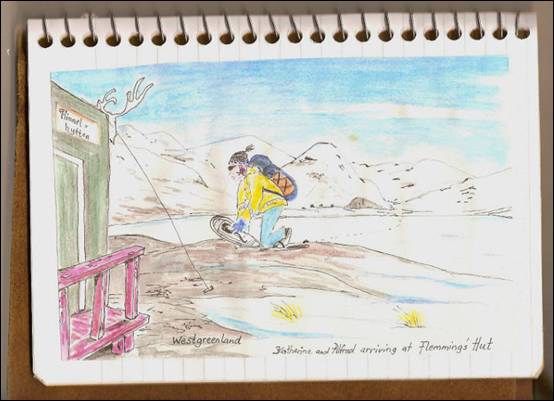

Gradually, the hut grows closer. The straps of Alfred’s pack are rubbing his shoulder, so he stops to pad the contact spot. I continue to trudge along, the end goal in sight – like a horse homeward bound, not much will stop me now.

With relief, we climb the wood steps, dumping our backpacks on the deck. After 14.5 kilometers and 8 hours on the trail, we are happy to call it a day. It’s a cozy cabin, fastened to bedrock with steel cables and pins at the outside corners. Inside, there are three rooms: kitchen with propane stove, pots, spice rack, sink, a bedroom with double bunks lined with foam mattresses, sleeping bags, pillows and large common room with single cots, table, overhead drying rack. A curtained toilet with plastic bag liner sits just inside the main door. There is no electricity, but fat white candles dot window ledges, table tops and various level surfaces.

It takes a while to get the propane kitchen stove going – after locating the ‘on’ toggle outside, the cabin interior heats up quickly from –5C to +20C. I chip ice from the lake into a pail, then using the largest kitchen pot, melt it into drinking water. Much faster than using the tiny trangina stove. Coffee is quickly made, even before we take off our boots (sweat wet inside). We lounge on the cots, snack on oatmeal before heading out back outside for a short stroll to inspect the grounds.

The area surrounding the cabin is so neat, unlike many remote cabins I’ve come across in the Canadian arctic. Instead of trashing laying around, an oil drum has been set up to burn garbage. An aluminum canoe is overturned, set tight against winds, in a rock groove.

Without the weight of a backpack, it’s a joy to explore – plants get closer inspection, rock humps beckon walking, the slope ‘just over there’ is never too far. Low growing crow berries, their fleshy purple fruit still attached to the plant, wait to be picked, tart on my tongue. Happily, we explore until satisfied.

A sudden gust of wind yanks us away from our revelry, an unexpected hard shove coming from nowhere. A second powerful blow has us back tracking to the cabin. We latch the door closed, the wood walls already vibrating with the increasingly intense gusts. The metal communication tower and its steel cables vibrate and hum. The wind clears any loose snow from the frozen lake as well as blowing any fluffy snow away from the slopes. The newly exposed lake ice appears as dark patches against white snow. But its warm inside the cabin, and by 10pm, despite the wind shaking the walls and shrieks as it whistles around outside, I’m pretty much sound asleep.

Arrival

at Flemming’s

Hut

Arrival

at Flemming’s

Hut